Chronicles of Changing Times. The Cinema of Edward Yang

According to a well-known anecdote, Haruki Murakami only began writing fiction when he was twenty-nine. When watching a baseball game, he suddenly had an epiphany that he could write a novel. After that he went home and started writing, giving birth to his first book nine months later. Like Murakami, Edward Yang (1947-2007) had a similar flash of insight at a similar age when he came across Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972). This film became a powerful inspiration, reminding him that magnificent films could be made without an extravagant budget. So the story goes.

When growing up, Yang thought he would “please his parents” and traveled a path that would lead to conventional successes. After receiving his graduate degree in electrical engineering from the University of Florida in the mid-1970s, Yang stayed in the US and worked as an engineer for seven years or so. When he turned thirty, he found himself to be less certain than ever about the kind of life he was heading into, and soon decided that he ought to at least pursue one of the fields that he had been deeply passionate about: architecture or filmmaking. Upon receiving admission offers from several prestigious architecture schools (including Harvard and MIT), he met with a close friend who posed the question: “Would you still want to make films even after being an architect for a while?” He finally realized what he really wanted. (Unsurprisingly, knowing or not knowing what one really wants became a consistent theme in several of his films.) Having made up his mind, in early 1980s he came back to Taiwan and launched a twenty-year career that was only too short for his immense talent and brilliance. As a leading figure of the Taiwan New Cinema—inaugurated by the omnibus film In Our Time (1982)—Yang conducted a series of marvelously unyielding inquiries into the trials and tribulations of contemporary life in Taipei through seven and a quarter feature-length films.

Importantly, his many years of scientific training were not simply left behind after the “turn” toward filmmaking. Analytical precision forms an essential part of his subtle yet distinct style— a kind of intense rigor that does not content itself with the so-called mind games that one often finds in cheap mysteries or psychological thrillers. Underlying his artistic vision, perhaps, is a search for a more pervasive and original form of rationality that has sensibility already as a part of its constituent core. His visual compositions illuminate a hyperawareness that geometrical figures are closely linked to intuitive knowledge; his play with sound often gives rise to moments of surprise, jolting us out of habitual association or perception, the naturalness of which we have long taken for granted. In this way, his demand for formal and narrative exactitude yielded a style that is often described as sober, distant, cold and challenging.

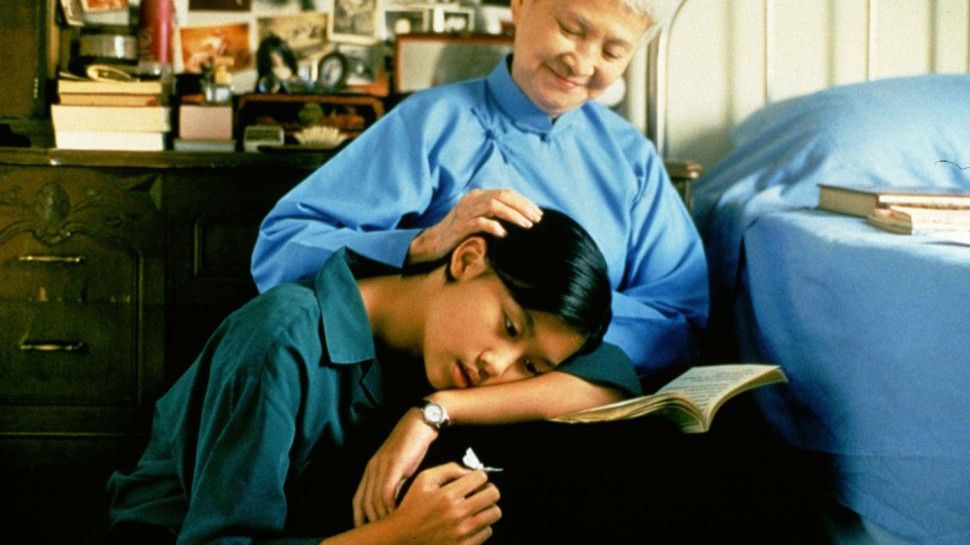

The narrative worlds that Yang’s oeuvre constructed crystallized into a cinematographic form of history of the development of Taiwan in the second half of the 20th century. The diegetic space of A Brighter Summer Day (1991) is the earliest: the story is based on a true incident, a murder that took place in 1961. The film was made shortly after the loosening of governmental censorship, when Taiwan’s history became a permissible subject for more open discussion and reflection, but the original uncut version was not screened publicly in Taiwan until 2007. The lost and confused adolescents in this film, who struggle to find a sense of belonging and identity, will have grown into the same age as the adults or parents in the world of Yang’s last feature, Yi Yi (2000), set in contemporary Taipei at the turn of the millennium. Time has passed and much has changed, yet the difficulty in grappling with the full meaning of life persists.

The only other period piece is his first short film, a segment titled Expectations in In Our Time, which marks its own diegetic time with a subtle reference to Beatles’ Japan Tour of 1966. Even though few of his works are set in the past, Yang’s contemporary films carry a poignant presentness which is deeply rooted in the history and changes of Taiwan. His first feature film, That Day, on the Beach (1983), through complex flashbacks and flash forwards, depicts a narrative that spans from the late 60s to early 80s. Along with Taipei Story (1985), these three early films foreground female interiority in a Taiwan undergoing drastic socioeconomic changes.

One of the questions persistently posed by Yang’s films is: in changing times when one’s values are constantly undergoing reconstruction, elimination and assimilation, how can people keep their own character and ideals intact while remaining adaptable and fit to live in harmony with the new moment? His continual experimentation with different film and literary genres such as melodrama, comedy, epic and tragedy as well as with different artistic media, including theatre, music, drawing and animation, shows his own efforts in reflecting on this question. His last three films—the “New Taipei Trilogy”—A Confucian Confusion (1994), Mahjong (1996), and Yi Yi, orchestrate intricate narrative mosaics with playful stylistic explorations. The first two of this group are among his less-known films, which not only depict explicitly and fiercely the impact of capitalism on personal relationships in Taipei and the challenging role of tradition in an increasingly multicultural metropolis, but also poignantly expose a pervasive spiritual emptiness and intellectual timidity which generate unfortunate or terrifying consequences.

In an age when “grand narratives” are called into question, Edward Yang did not hurry off to celebrate any facile sense of freedom or independence. His relatively small, yet tremendously important, cinematic corpus (sharing the same number as Andrei Tarkovsky’s) warns us of the encroaching void and compels us to continue reflecting on the fragile relations between a private self and public conventions. Yang loved Taipei deeply, but like any true friend, he would never be its mere flatterer. In exposing the problems associated with urban alienation, the dominance of capitalist and materialist thinking, and the increasing opacity of human intimacy, he let the city of Taipei, with its unique history and complicated identity, become a marvelous site for the world to contemplate perennial questions such as the meaning of life, the pursuit of happiness, the knowledge of the self, and the challenges of the individual’s navigation with broader social forces.

Within the span of just a month in 2007, Edward Yang, Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni passed away. Even though Yang had been far less recognized than the other two, a worldwide effort to acknowledge the significance of his cinema had been under way in recent years. In related but different ways, all three cinematic masters were concerned with civilization and its discontents. Epitomizing a sharp sensitivity to both the magic of film form and the power of narrative possibilities, their works speak to different strands or moments of modernism. They make visible the unending transformations and turmoil of the human psyche in the midst of change: difficult, terrifying, at times exciting, but always inevitable.

But the brave souls will keep soaring in the sky. As Edward Yang’s epitaph reads, “Dreams of love and hope shall never die.” – Ruochen Bo

The Harvard Film Archive is pleased to welcome Kaili Peng, the wife of Edward Yang, and Sean Yang, their son, to introduce the first two screenings of our retrospective. A world-renowned pianist and composer, Peng collaborated with Yang on his late films and has worked tirelessly to preserve his work and vast archive of materials spanning his entire career.